The possibility of failure is essential for a game of Dungeons and Dragons. The randomness provided by dice adds tension and affects the narrative direction, and the tension wouldn’t exist if there was not the chance of failure. As the Dungeon Master, you will be describing many of these failures. In this guide, we will take a look at why how describing failed skill checks is important.

No matter how a roll is failed, when describing the failure we want to maintain the player’s agency and more crucially, their characters’ competency. If we don’t do this, we can leave the player feeling bad about their attempted action.

To describe failed rolls successfully, we need to understand the context of the action, because as DMs, that lets us know how to describe a failed roll.

Context is Everything

The nature of having dice decide the outcome of skill checks leads to an awkward situation though; a character that is supposedly a master in their profession or skill can fail a mundane task.

For the sake of the examples below, we will assume that any skill check attempted will result in a failed skill check.

In order to describe failure in a way that preserves the character’s agency, we need to first understand how much risk is involved in the action.

As an example, a level 10 rogue should easily be able to pickpocket an everyday farmer. In this situation, not much is at stake, either because the situation is low-risk or because the rogue believably wouldn’t fail. Contrast that with the same rogue trying to pickpocket something from a master thief. It’s not that it can’t be done, but the action certainly isn’t effortless.

Let’s assume that both sleight of hand attempts fail. Importantly, in the case of the master thief, it is believable to have failed the pickpocket.

That doesn’t mean that there shouldn’t be the risk of failure for pickpocketing the farmer, but if we don’t handle it correctly, we can leave the player feeling demoralized and their character looking incompetent. To combat this, we want to describe lower risk failures, not as a failure of the character, but rather, a failure brought about by external forces.

In order for tension to exist, there needs to be weight behind succeeding and failing a roll, so we still need there to be consequences for failed actions. But we should treat these failures with the concept of failing forward, for both the narrative and the player.

Let’s look at a more in-depth example of how the description of a low-risk failure impacts the play and overall feel of the game.

Examples of Describing Failed Rolls

We will set the scene, dice rolls, and stats. After that, we will examine two ways to describe the low-risk failure:

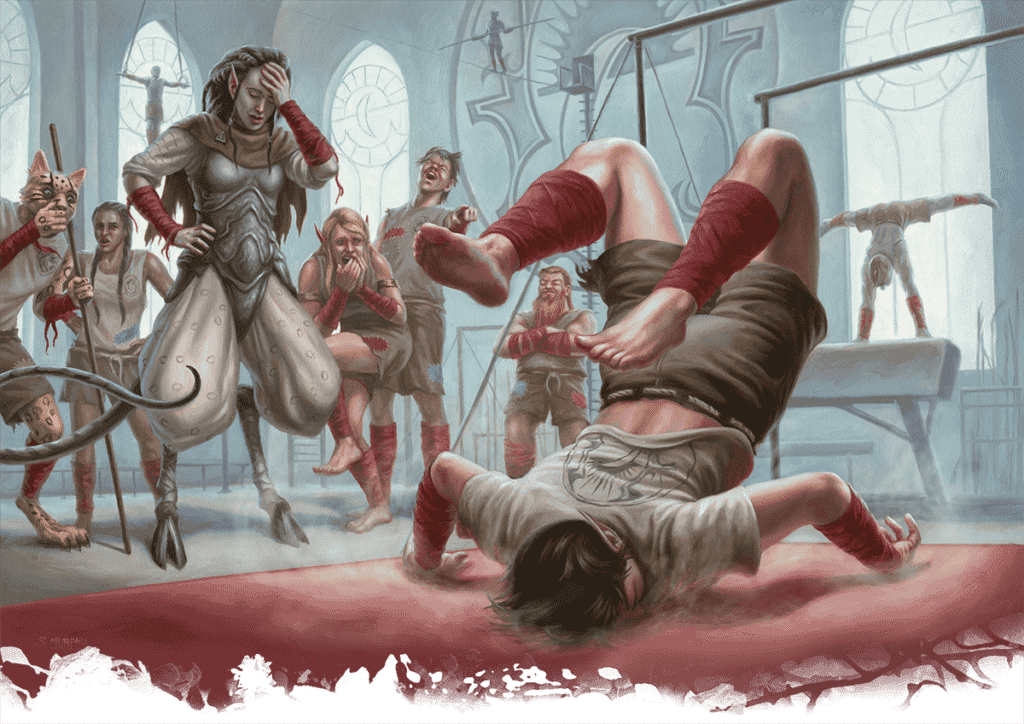

The party’s monk is sneaking into the villa of a rather corrupt politician and needs to bypass the walls to let the party inside the gates so they can catch the villain red-handed! The monk has chosen to do so by jumping from an adjacent rooftop, over the walls, and onto the roof of the villa. As expected, the monk says, “I jump from my roof to the villa’s!”. The monk has all the strength needed for a horizontal long jump to leap across the gap between roofs. So the distance is of no worry, however, the roofs of the villa are rather steep so you call for an acrobatics skill check for the landing.

Oh no! The player rolled a 2, let’s say they have failed the DC and now it is up to you, the DM, to describe the failed landing. Remember, we are trying to preserve the competence of the player character — we want to find a way to encompass the random nature of the dice, and the negative outcome that doesn’t leave the player feeling as if their character is somehow silly or that they are shamed for attempting a relatively mundane leap.

All too often I hear descriptions and following narratives like this,

“Your jump misses its mark and you fall into the street below with a crash. The sounds of barking dogs fill the silent night. Lights in nearby shops turn on and the villa guards rush to inspect the scene…”

This description takes the narrative intent out of the hands of the player and can make the monk player feel removed from the narrative. We may have also inadvertently redirected the narrative in a way that the players may not have wanted.

While there is nothing wrong with a high-risk action and roll causing a more high-risk outcome in the narrative I would hesitate to classify our rooftop leap as high-risk.

Let’s say that we describe the failure another way that paints the character in a more competent light but still has a negative impact on the narrative while leaving the players in charge:

“You leap to the villa’s rooftop and as you land one of the roof tiles gives way under your foot. You manage to hang on but the loose tile slides off the roof and into the shatters on the cobblestone courtyard below. The voices coming from a nearby open window stop abruptly…”

The action was a failure, and for that failure, the situation is riskier as the guards within the villa might be more on edge, however, we have also preserved the narrative intended by the players as they enter the villa. We have not redirected them down some undesired side path as a result of their failure.

More important still, we have described the failure of the character without sacrificing their competency. The monk still made the jump and did so as expected. However, something went wrong.

In this way, our new description of the low-risk jump is not as a failure of the character themselves, but instead a failure of the situation to be ideal for the action.

This also adds an opportunity for the party or characters to solve the new less than ideal situation. The party could use a spell to simulate the sound of cats fighting or start to shout drunkenly at one another in the street to draw attention away from the crashed roof tile and the monk. They now have multiple options to pick from.

Often, in low-risk situations, we should be giving more opportunity for the players to act and solve problems in their own way, so the narrative shouldn’t close off too much as a result of a failed low-risk action.

Ultimately, this roof-top jump situation is all about context. The jump should be easy, therefore, we can assume it will happen, however, there might be unexpected obstacles as a result of a failed roll.

High-risk Skill Checks

What about failures for actions that are not low-risk like our rogue pickpocketing the master thief?

We should be describing those with the same level of risk and tension that the action warrants. While context still matters with these high-risk actions, we don’t need to do anything too special to describe them.

If a fighter is scaling a cliffside in the rain at night, then the situation is inherently dangerous and high-risk. Sure the fighter has their strength, but unless they have climbing gear in their backpack the fighter might outright fail to grab the next rock or lose their footing.

If the fighter fails an athletics check and begins to fall, all of that is believable. The failed roll doesn’t reflect poorly on the fighter, because scaling a cliffside in the rain is hard.

If you’re having any trouble deciding if an action is a high or low-risk action, use the DC as a good guide. Anything below 10 could be considered low-risk. Sure, we are rolling, but less to see if the character can pull it off and more to see if the situation will lead anywhere. Opposite that, with DCs above 10, high-risk actions are hard to pull off, so we roll to see if we can.

At the end of the day, as DMs we want to avoid a situation where a failed skill check closes off portions of the narrative in an unbelievable way. If a failed attempt leaves the situation drastically changed, the players could develop an aversion to attempting things they feel are too risky.

Alternative Ways of Describing Failed Skill Checks

Another thing we can try is letting the player describe their failure. It allows them to maintain their character’s identity and competency (we hope). This is a great tactic that allows the player to drive the story of their attempt. Granted, they failed, but how they spin that — no one has a better idea of what their character does and fails like than the player. A proper concern with this approach is if the player is new and doesn’t quite have things figured out and they may need to be eased into the idea. Perhaps a more urgent concern is that the player improperly involves another player in a way they do not want, resulting in the exact thing we set out to correct.

Ultimately, as the Dungeon Master, you are a mediator. You play the part of the world and for the most part, the players should feel respected in their decisions. If they are yelling at the table, it should always be at a character, NPC, or villain, never at a person. The purpose of the possibility of failure within the game develops tension and narrative uncertainty, however, a failure should not close off every branch the players may be attempting to go down.

Final Thoughts

If we are too careless we can leave the player feeling bad about their attempted roll. A failed roll shouldn’t be a punishment; the challenge might grow or the tension might arise, but the player shouldn’t feel bad for trying something that didn’t work, rather they should feel encouraged to try the next thing.

At the end of the day, the choice is yours. Don’t be too stressed if you’ve described failure well or not — it’s a hard skill and not easily mastered. Instead, keep it in your toolbox and apply it when you think you need to. Keep open to feedback from your players as well.

We must not forget that the story is dictated by the players. Their ability to engage and feel as if they have agency is one of the most important things to preserve during your time at the table.